Višnja Pavelić: The daughter of a Croatian dictator who lived as a recluse in Madrid

The 92-year-old woman worshiped her late father, Ante Pavelić, whose regime was responsible for the genocide of more than 300,000 people in the Nazi puppet state of Croatia. Before her death, she invited us into her home where there was no remorse, only a deeply entrenched hatred

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/XK4FZR4Z5TJDBMKKHBG2ICCO5A.jpg)

Before her death in 2015, Višnja Pavelić, the daughter of the Croatian dictator Ante Pavelić, lived alone in a gloomy Madrid apartment. The blinds were invariably lowered and the curtains drawn. For 50 years she worked tirelessly in this perpetual twilight on her father’s archives in a room filled with towers of shabby files. The only break in her routine came in the afternoon, when she would rest on the sofa and put on a record of Verdi or her favorite baritone, Gino Bechi.

Ante Pavelić was given refuge by Spanish dictator Francisco Franco and lived the last two years of his life in Madrid where he died in 1959. His fascist rule was sponsored by Nazi Germany with Serbs, Jews, Roma and opponents persecuted and sent to death camps between 1941 and 1945, where more than 300,000 were killed, according to the US Holocaust Museum. “It was a monstrous regime and he was its leader. For me, he is on a par with Hitler,” says Hrvoje Klasic, a historian at the University of Zagreb.

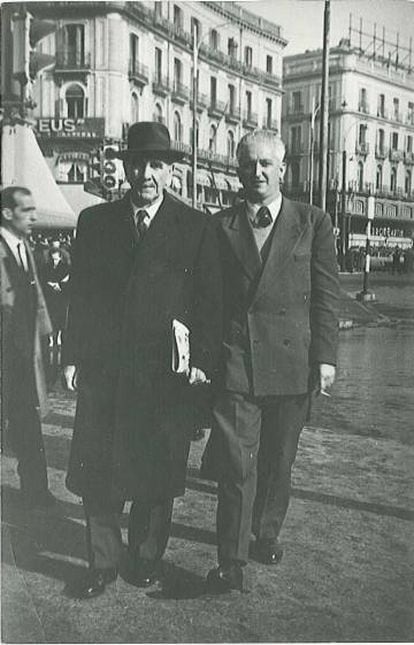

Pavelić spent the last years of his life strolling around Madrid. In an unpublished photograph from that period Višnja showed to EL PAÍS Semanal, he poses at the popular Puerta del Sol square, dressed soberly in a hat and a long, black overcoat. As an old man, he looks harmless – a far cry from the cold, tense and overbearing figure of the 1940s. And while his distinctive thick eyebrows and his enormous ears, with lobes that hung like steaks, remained, he had let a mustache grow.

When he died at the age of 70, the Spanish news agency Cifra reported in brief that he had been buried in the San Isidro cemetery in Madrid “during a funeral ceremony in the strictest privacy,” with no further description of the man other that he had been “head of the Croatian state during World War II.” Spain’s ABC newspaper put his brief obituary at the bottom of a page under a section called “Echoes of Society,” which gave news of weddings and engagements.

“Do you want a little piece of chocolate?” Višnja asked.

The dictator’s daughter was serious but friendly and polite, always using the formal address of usted. She welcomed me into her home several times in the years before she died, seeming to welcome the company and to enjoy talking about her father, although she made it clear that she didn’t want any of what was said to be published until several years after her death. Every time I left her apartment, she would accompany me to the door, her frame small and hunched, saying “But all this before my death, nothing, eh, nothing!” Her Spanish was heavily accented and carried with it nuances from the family’s exile in Argentina.

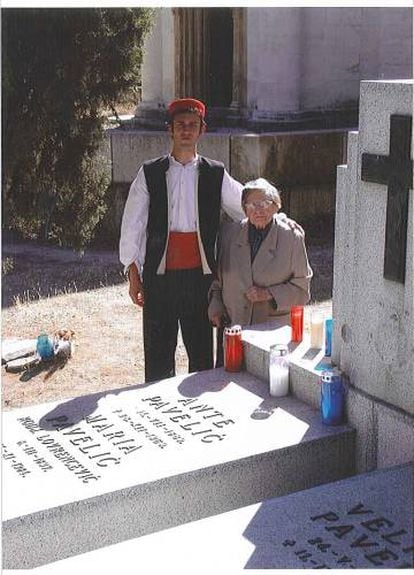

Višnja was obsessively discreet. She did not want people talking about her or photographing her and she watched over her father’s grave zealously. According to Almudena Moreno, in charge of the San Isidro cemetery, “She went with a little fold-up chair and spent her afternoons protecting his grave.” Fearing the desecration of the site by Serbs, she placed a heavy tombstone over it and asked the cemetery to reveal nothing of its location to strangers. “She seemed panicked,” said Moreno. “I told her, ‘Don’t worry, they won’t come to Spain to look for him.’” Her fears were so deep-rooted that she contacted the Ministry of Justice before she died, to prevent any future exhumation of her father’s remains.

Višnja Pavelić died on Christmas Day in 2015, at the age of 92. She was cremated, and her ashes were placed in San Isidro cemetery where the rest of her family’s remains lay.

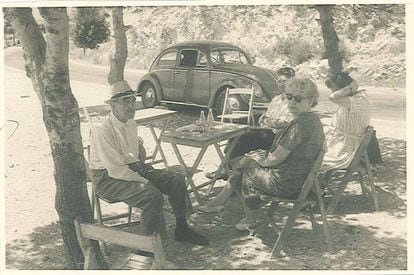

Before her father’s death in 1959, Višnja loved to have photos taken during family outings. One such photo is taken in the coastal town of Santa Pola, in the eastern region of Valencia. Višnja is smiling while her brother Velimir's expression is formal but kind. Their mother Maria is wearing sunglasses and a tight smile while the former dictator wears an expression with a steely quality reminiscent of the younger man and an earlier time. Also of note is the air of austerity about the family despite the suspicion that they fled Croatia armed with a fortune stolen from both Pavelić’s victims and the state.

In the book, Croatia Under Ante Pavelić, the historian Robert B. McCormick writes that Pavelić was able to divert millions to Switzerland during the war. He mentions a CIA report on the war’s final stages and the fact that Pavelić sent 12 boxes of gold and jewels to Austria with a view to his own exile as Adolf Hitler was being brought to his knees.

The photo in Santa Pola would have been taken 14 years before the family was snapped in the shade of some pine trees by their Volkswagen Beetle. Višnja could not remember for sure where they were, but she thought the photo might have been taken during their last outing with their father in 1959, when they visited the newly opened Valley of the Fallen monument in the north of Madrid. At that stage, Pavelić looks frail, with fallen shoulders and a far-off gaze, like Vito Corleone in the cult film The Godfather, before he meets his end.

Corleone and the Croatian tyrant both died of old age, having survived assassination attempts. The Sicilian mafia leader was shot while buying oranges at a New York street stall and Pavelić also took several bullets when coming back to his home on the outskirts of Buenos Aires in 1957. “He walked in and said, ‘I’ve been hit,’” Višnja recalled. While no one knows who was behind the attempt on his life, there was speculation that it had been the Yugoslavian dictator, Josip Tito, though Višnja dismissed this. “The Serbs asked for his extradition; they wanted him alive,” she said. In her view, it had been orchestrated by compatriots hoping to gain control of the Croatians diaspora.

At the end of World War II, in 1945, Pavelić escaped to Italy, where he hid in a Jesuit monastery. “No one ever knew about that. Only us, ha!” said Višnja. In 1948, Pavelić went by the name of Antonio Serdar and took a boat from Italy’s port city of Genoa to Argentina, using the so-called “ratline” taken by Nazis like Adolf Eichmann, Klaus Barbie and Josef Mengele to Latin America. For the next 10 years, the family lived in Buenos Aires with the permission of the Perón government and Pavelić set up a construction company. He also had a weaving loom and a farm. “We had chickens,” Višnja told me. “I collected the eggs in the morning.”

During our talks, Višnja sat on the sofa in the living room under a charcoal portrait of her father, who is drawn with neatly combed hair, a white jacket and a sullen face.

“You don’t think he’s to blame for anything?” I asked.

“No, not at all,” she replied.

Initially, she would get up every so often to look for documents to try to prove that her father had not been as despicable as history paints him. Even when she became crippled by osteoporosis, she would reach for her files and repeat, “It’s all a lie. Everything they say about my father is a lie. Everything, everything.”

The Independent State of Croatia, established by the Nazis after their invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941 and led by Pavelić until 1945, was driven by the goal of ethnic and religious purity – Croatian and Catholic. At least 83,145 people were killed in Jasenovac, the country’s largest concentration camp, according to official data; among them 47,627 Serbs, 16,173 Roma and 13,116 Jews with 20,101 of the victims children under 14. The ustasa, as Pavelić’s ultra nationalist revolutionary movement was known, killed with a ferocity that shocked even their Nazi allies. In the book Ustasa, the historian Srdja Trifkovic tells how General Von Glaise-Horstenau, the Führer’s military representative in Croatia, said that Pavelić’s “revolution” had been “by far the bloodiest and most horrible” of all those he had seen.

Meanwhile, according to historian Robert McCormick, “inside the infamous Jasenovac [concentration camp], thousands of men, women and children were slaughtered with bullets, axes, hammers and every other tool at hand.” The murderous appetite of the ustasa was only comparable, he says, “to that of the most manic members of the SS in the Third Reich,” in reference to the Schutzstaffel paramilitary organization.

In the book, 44 months in Jasenovac, concentration camp survivor Egon Berger recalls the atrocities in detail. “The echo of horrific screams pierced the room as Milos slit his body from top to bottom, then slit his throat,” he writes. “One of the ustasa, a 12-year-old boy, took out his knife and cut off the priest’s ears.” And also, “While the Germans poisoned their victims and then burned them, the ustasa threw living humans into the fire.”

“Jasenovac is a complete exaggeration,” said Višnja. “It was a labor camp, and there was poverty, but they had doctors, their own leaders, everything they wanted. It wasn’t Auschwitz, understand? They were all alive and well.”

Of all the monstrosities attributed to her father, Višnja was especially upset by an anecdote told by the journalist Curzio Malaparte in his book Kaputt. Malaparte, who tended to spice up his stories, describes an interview with Pavelić in his office in which the dictator, wearing military attire and riding boots, had a wicker basket on his desk with the lid half open. According to his account, Malaparte thought he could see fresh shellfish inside and asked if they were oysters from Dalmatia. “Ante Pavelić lifted the lid of the basket, took out a handful of slimy and gelatinous oysters and, throwing me one of his weary smiles filled with kindness, said, “It is a gift from my faithful ustasa: 20 kilos of human eyes.”

“Ha!” exclaimed Višnja. “What that man says is unbelievable! All false! It’s all false!”

On the table, she had a book titled The Holocaust Industry and the three newspapers she bought every morning, EL PAÍS, El Mundo and ABC. She insisted that her father had been “neither a Nazi nor a Fascist,” but a nationalist who fought “for the liberation of Croatia from Serbian rule.” Rather than cynical, she seemed blind.

Hers was an attitude common among the descendants of Nazi leaders. In her book Children of Nazis, Tania Crasnianski writes, “When it comes to children, mental defenses are indeed very strong. Gudrun Himmler [the daughter of Nazi police chief Heinrich Himmler] has always been characterized by a total lack of perspective towards the father figure.” Similarly, “Edda Göring [the only child of Nazi military leader Hermann Göring] had an unwavering love for her father and refused to see him as one of the instigators of the Shoah [Holocaust].” Like Višnja, Edda “lived barricaded into a small apartment in Munich and the apartment was a museum to glorify the man.” In the same vein, Wolf Rüdiger Hess – the son of Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess – always idealized his father and “never stopped thinking of him as a messenger of peace.”

In Buenos Aires, Višnja became her father’s confidante. After the attempted assassination, she organized his secret passage to Spain. In Madrid, a Croatian priest told her that the Spanish chancellor Fernando Maria Castiella had given the green light to Pavelić’s arrival on one condition – “Ask them for just one thing, Father: discretion,” the chancellor was meant to have said.

In Madrid, the family rented an apartment close to the city’s popular Retiro park. Višnja went out daily with her father for walks in the park. She organized his papers and contacts with the Croatian diaspora. In the last photograph that was taken of him, Ante Pavelić is sitting down, staring absently into space with a hand resting on his temple while his daughter, dressed in black, stares hard at the camera.

After his death, Maria, Višnja and Velimir stayed put until 1961, when they moved to the apartment where they would spend the rest of their days. Maria, the mother, cooked, sewed and took care of the house. She died in 1984. Velimir played the violin and spent hours shut up in his room reading books on philosophy and political history, writing aphorisms and chain smoking. He died of lung cancer in 1998. The apartment was in the Concha Espina neighborhood, near the Santiago Bernabéu soccer stadium. Višnja said that on weekends you could hear the roars of the crowds when the team Real Madrid scored, but none of the Pavelićs ever ventured out to see a game for themselves.

They lived off the rights to Ante Pavelić’s writings and donations from exile organizations based in countries such as Canada or Australia. Višnja was her father’s symbolic heir and his tomb became a shrine for those nostalgic for the ustasa. During the Balkan War, Croatian militiamen sang: “In Madrid there is a golden tomb and in it lies Pavelić, the leader of all Croatians. Rise, Pavelić, we will all die for you.”

Every time a Croatian soccer team played in Spain, some of the more radical fans and even the soccer players themselves would visit the cemetery and would seek Višnja out to pay her their respects. In another photograph from her personal collection, she is shown at the grave accompanied by a young man in traditional Croatian dress. Small and bird-like, she was still an unrepentant ultra-nationalist who expressed a genocidal hatred of the Serbs: “They are born criminals,” she said. “There is no Serb who is not a criminal. They have done nothing but kill! Nothing else. Killing is genetic in them, and all we have done is defend ourselves.”

The last time I saw her, she could hardly move and wore a senior citizen emergency button around her neck. By then she was barely talking to anyone other than her cleaning lady and a niece based in Ontinyent, Valencia, who sometimes went to visit her.

On my last visit, Višnja told me that a Croatian researcher had taken three trunks of documentation on Ante Pavelić from her home to bury in Croatia.

“Why bury them?” I asked her.

“So that everything will be safe,” she answered. “Underground, everything will be safe.”

Then she handed me the last picture taken of her father. It was of the body of the dictator in the German hospital of Madrid, lying on a bed with a bouquet of flowers across his legs. His face has about it the rigidity of death but the ominous black eyebrows and enormous ears are the same. Above his body is a crucifix and, to the sides, two candles burn while a weak winter light enters through the window.

“It was very difficult to be this man’s daughter,” said Višnja Pavelić. “Very difficult.”

English version by Heather Galloway.