Mark Lanegan’s memoir: A junkie’s equivalent to porn

How one of grunge’s biggest stars hit rock bottom and, eventually, got back on his feet

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TSXQDGJXXJBBRNBFNBU54VRP2U.jpg)

I remember when there were only two types of musical fans in Spain: one group was hooked on the crooner Raphael and the other, to somewhat sparkier bands – and yes, most were female.

Now, thanks in part to social media, all kinds of artists have fans of both sexes, and they can be quite militant in the defense of their idol. This is particularly the case when the idol is revealing a litany of dubious acts and woes in their personal life: in this case, the fan insists that this aspect of their idol is irrelevant; what matters is their work. They are deaf to the argument that a person’s songs reflect their lives, from the mildest to the wildest, not to mention the conditioning influence of money and contracts. All you are doing, they rail back, is contaminating the artistry.

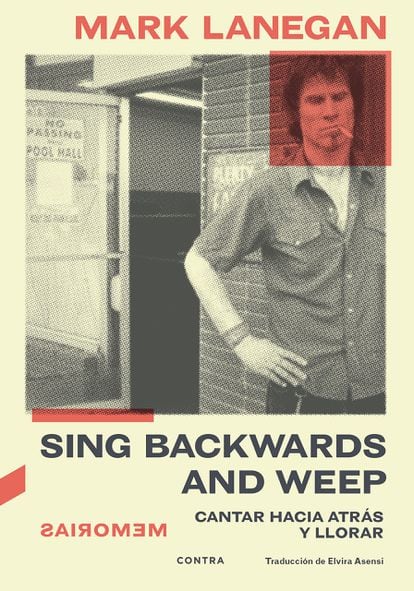

I wonder what Mark Lanegan fans will have to say when they read Sing Backwards and Weep, the musician’s harrowing memoir, recently translated into Spanish as Cantar hacia atrás y llorar by Elvira Asensi for Contraediciones. It is a tome so dark that it seems designed to make us hate both its author and his music. But Lanegan’s chronicle of horror ends around 2000, when he begins his most impressive creative stretch as a soloist and, also, in collaboration with other musicians. Implicit in the text is a well-worn excuse for the author’s bad behavior concerning the sins of the father: in Lanegan’s case, a merciless mother and, to a lesser extent, a distant father, turning him into the Tennessee Williams of the grunge era.

In fact, Sing Backwards and Weep belongs to that popular subgenre of rock autobiographies: my-hell-with-drugs, the junkie’s equivalent to porn. Unusually, however, there’s barely any mention of redemption: for years, he continued to consume and we might imagine that it also took him a while to turn his back on his particular poisonous strain of masculinity.

Lanegan was the lead singer of the Screaming Trees, grunge’s second division, though he supposedly hated their music and even more viciously, his bandmates. He did not recognize that a coincidence of time and place allowed them to be part of the Seattle rock movement. Admitted into the musical aristocracy of the northwest, he became close to Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, and Cobain’s wife and Hole singer, Courtney Love, as well as members of the band Alice in Chains. He could be considered an accomplice in the death of some of them, but, lucky for him, the survivors threw him a lifeline. Or three.

Big and loud, Mark Lanegan was predictable at first; an alcoholic with an impressive sex drive, but then he switched to heroin, methadone and crack – not just their consumption but also their distribution. The brutality with which he mistreated his own body impressed even Nick Cave when he went to his house to score. It was a kind of open house, but despite that, Lanegan was amazed that, during an absence, his collection of porn magazines and videos were stolen. At least, however, he wasn’t homeless yet.

Lanegan was sustained by his rabid animosity for his supposed enemies, from the founders of the Sub Pop label – unforgivable that they took a portrait he didn’t like for the cover of his first solo album – to Matt Dillon – in a chance encounter, he surreptitiously slipped a lit cigarette into the actor’s jacket pocket. Dillon’s sin: having been in Singles (1992), a banal romantic comedy about the Seattle scene. It is a film that Lanegan had not seen; presumably, he was unaware of the existence of Drugstore Cowboy (1989), a drama starring Dillon about the risks of opiates.

One suspects that Lanegan embroidered the truth more than a little in Sing Backwards and Weep. His seething imagination allowed him to (re)construct humorous conversations and situations that lighten his many misadventures – like the pathetic wrangling with Liam Gallagher. The height of this tragicomedy is Lanegan’s search for heroin on the streets of Amsterdam in the middle of a winter’s night with no money, having been mugged.

I won’t give away the end, though it’s worth knowing that Lanegan got himself cleaned up, developed his career, got married and settled in Ireland where he was hit by the second wave of Covid-19, a disease he had previously dismissed, like so many macho rockers. He seemed to have overcome it and even wrote about it in his second book, Devil in a Coma. But he passed away on February 22nd of this year. The actual cause of his death was not revealed.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/QMVDCSA67JBUTNLMFA3XJHGVFE)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/JFNVTYEIGNEJHIPT76WAP26OQY.jpg)